A project accomplished on 3/4/2012 by the San Antonio and Austin Astronomical Societies,

Ron Peters, Robert Reeves, Keith Little, and George Cooper in collaboration with the

National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) and Astronaut Don Pettit.*

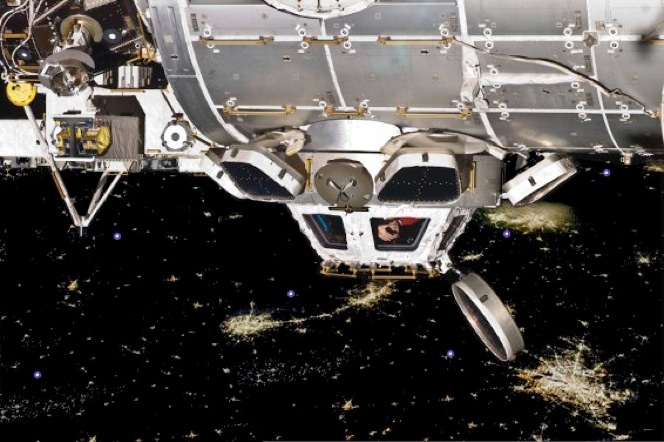

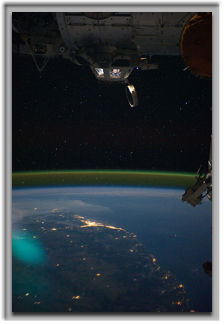

The Cupola on the International Space Station where

Astronaut Don Pettit took the photographs from.

Ron Peters successfully contacted the ISS (International Space

station) using searchlights which was verified by NASA

Astronaut Don Petit onboard the ISS!

This was a project Ron did on his own personal time in

collaboration with the San Antonio Astronomical Association, Austin Astronomy Society, Robert Reeves, George Cooper, Keith Little, Don Pettit (astronaut), the National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA), and the Lozano Observatory in Spring Branch, TX.

Ron used 2 small searchlights loaned to him by an outdoor promotions company Ron was working for at the time. Ron’s

boss at the promotions company didn't want to devote any

company time or money in this project due to numerous other

projects the company was working on at that time, but after an offer by Ron to do it on his own time, Ron was allowed to borrow the 2 Lights used in this event. Ron even travelled to Spring Branch, TX and drove his ugly blue van up some pretty treacherous gravel and dirt roads to reach the observatory where the event took place!

!["I was ready with cameras for the

early morning San Antonio pass,"

said Pettit. "And [I] can report

that it was a flashing success."](ISS_Flash_Project_files/shapeimage_8.png)

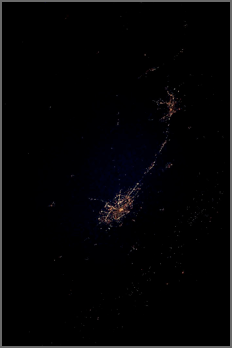

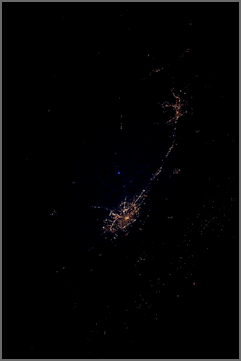

Sequence of “light on / light off” Photos.

The BLUE DOT in the 1st and 3rd photos is the Searchlight !

(3 of 9 total photos taken by Don Pettit on board the International Space Station.

ALL 9 photos were provided to the media and many other websites and are public domain.)

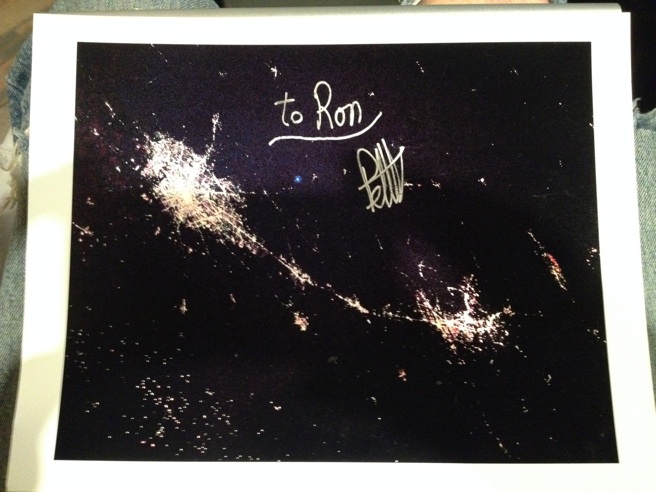

Astronaut Don Pettit

On March 4, 2012, about 65 amateur astronomers were in position at the Lozano Observatory in Springbranch Texas. They turned on the searchlights and waited as the ISS was set to make an appearance in the sky. At the precise time, they began flashing the two searchlights at a rate of two seconds on, then two seconds off, in a very non-technical, but effective manner.

“We had two people manually aiming the lights and two people holding plywood up over the lights, and they were manually tracking the space station,” Keith Little said.

Don Pettit, meanwhile, had no trouble seeing the flashes.

“Don sent us an email the next day,” Little said, “and he told us how bright it was, and how he could see the lights even before we started the flash system. He saw it from 10 degrees above from the west to 10 degrees from the Northeast.”

To everyone’s surprise, Pettit could also see the blue laser. “When the spotlights were off, he said he could still see the blue laser, which was shone steadily,” Little said. “I was pretty surprised that the laser light was that visible from space.”

Little ran the laser and he had three people aiding him by watching for aircraft, “It is an FAA offense to shoot an airplane with a laser, so we took all the safety precautions so that we wouldn’t take that chance,” he said.

But if you see the ISS passing overhead, don’t expect that you can flash a light and they will see it. For one thing, they probably won’t be looking for your light. But additionally, Pettit explained in a previous blog post how when we see the ISS best here on Earth, they can’t see much below.

Ironically, when earthlings can see us, we cannot see them. The glare from the full sun effectively turns our windows into mirrors that return our own ghostly reflection. This often plays out when friends want to flash space station from the ground as it travels overhead. They shine green lasers, xenon strobes, and halogen spotlights at us as we sprint across the sky. These well-wishers don’t know that we cannot see a thing during this time. The best time to try this is during a dark pass when orbital calculations show that we are passing overhead. This becomes complicated when highly collimated light from searchlights are used, since the beam diameter at our orbital distance is about one kilometer, and this spot has to be tracking us while in the dark. And of course we have to be looking. As often happens, technical details complicate what seems like a simple observation. So far, all previous attempts at flashing the space station have failed.

But of course, now there has been a success.

Little said the two astronomy clubs put in 3 months of planning with several meetings, and thanks do the donation of the spotlights from Ron Peters, the costs to do the experiment were minimal. “We had lots of volunteers who wanted to be a part of it,” he said.

Is there any science in this, beyond knowing that under the right conditions the ISS astronauts could see lights from people on Earth?

“Well, if the ISS were to somehow lose all communication, which I would find hard to believe, we just showed that we could spot the station and possibly send them messages through Morse code,” Little said.

But Little said the main thrust of the whole event was the novelty of trying to be the first to successfully shine a light at an orbiting spacecraft that the crew could see, as well as trying to bring astronomy to the attention of the general public.

Nationality

American

Born

April 20, 1955 (age 59)

Silverton, Oregon

Other names

Donald Roy Pettit

Other occupation

Chemical engineer

Time in space

370 days

Selection

1996 NASA Group

Missions

STS-113, Expedition 6, Soyuz TMA-1, STS-126,

Soyuz TMA-03M, Expedition 30 Expedition 31

*All NATIONAL AERONAUTICS & SPACE ADMINISTRATION photos on this page are in the public domain

because they were solely created by the NATIONAL AERONAUTICS & SPACE ADMINISTRATION (NASA).

NASA copyright policy states that "NASA material is not protected by copyright unless noted".

(See Template:PD-USGov, NASA copyright policy page or JPL Image Use Policy.)

© 2015 North American Searchlight Advertising LLC. NASA Searchlights LLC All Rights Reserved.

![Did you ever use a flashlight to send a Morse code message to your neighbor at night as a kid? People like to say hello using lights and it's no different for space aficionados who want to twinkle a greeting from the Earth to the International Space Station during a sighting as it passes overhead -- except that it is a whole lot more complicated.

Although the space station has been in orbit for more than a decade, the first successful flashing of a beam of light to the laboratory happened only recently. On March 3, 2012, the San Antonio Astronomical Association met to attempt to shine a signal to the station. Aboard the orbiting lab, astronaut Don Pettit was watching and waiting.

"It sounds deceptively easy," said Pettit in a related blog entry. "But like so many other tasks, it becomes much more involved in the execution than in the planning."

The ground group used a one-watt blue laser and a white searchlight provided by Ron Peters to track the station as it flew overhead. Pettit worked via e-mail with the association members to run complicated engineering calculations to ensure they were accurately tracking the station. Considerations included the diameter of the light beam, the intensity of the laser, and the fact that the station is a moving target, as Pettit pointed out in another blog post on the difficulty of Earth photography from space.

"From my orbital perspective, I am sitting still and Earth is moving," said Pettit. "I sit above the grandest of all globes spinning below my feet, and watch the world speed by at an amazing eight kilometers per second [approximately 17,880 miles per hour]."

Pettit had additional complications to address to capture an image of the beam of light from the Texas fans of the space station. Even with a shutter speed of 1/1000 of a second, the camera he used on station was not fast enough to photograph the Earth below, which also is moving. To compensate for this, Pettit used precise manual tracking -- a technique of moving the camera along the same path as the object being photographed -- a skill perfected on orbit while working on Crew Earth Observations research.

While photographing the Earth may provide an entertaining pastime for the crew, there also are important research goals and benefits for those of us on the ground. It can take up to a month, according to Pettit, for astronauts to become proficient at taking this kind of planned image. The crew's photographic efforts can provide orbital perspectives of natural disasters and man-made alterations of the planet, which aid in relief and environmental efforts.

Preparing to capture the flash provided practice for Pettit in planning and tracking a specific Earth target. With the station circling the Earth every 90 minutes, you might think there is ample opportunity, but the circumstances of the pass had to align. Pettit and the team in San Antonio had to choose their timing carefully, selecting a "dark pass" when the station could see the ground, but those on the ground could not see the station.

"Ironically, when earthlings can see us, we cannot see them," said Pettit. "The glare from the full sun effectively turns our windows into mirrors that return our own ghostly reflection. This often plays out when friends want to flash space station from the ground as it travels overhead."

Planning took weeks for this particular event, between calculations and timing. That morning Pettit was excitedly waiting, camera in hand, for the precise moment. When the instant came, he was able to see not only the flash of light from San Antonio, but to capture a digital image showing the beam of light.

"I was ready with cameras for the early morning San Antonio pass," said Pettit. "And [I] can report that it was a flashing success."

by Jessica Nimon

International Space Station Program Science Office

NASA's Johnson Space Center

Houston, TX](ISS_Flash_Project_files/shapeimage_11.png)

Beaming Success for Station Fans